The Province of Ontario has featured some prominent tennis families over the years with talented offspring following in the footsteps of their parents. Recent sport science research suggests that neither nature nor nurture are independently responsible for these tennis bloodlines. Instead, it is a complicated “constellation of factors” that interact to produce elite tennis players.

The age-old nature versus nurture debate questions whether human behavior is determined by a person’s inherited genes or by the environment, either pre-natal or during a person’s lifetime. That debate has ended, according to the University of Ottawa’s Stuart Wilson who published a study about the relationship between an athlete’s skill level and the sport participation or expertise of their parents in 2019.

“It is neither exclusively one nor the other, but both,” said Wilson, a PhD candidate at the university. “Our research supports the view that it is a constellation of factors that interact and are dependent on one another. It is folly to try to separate nature from nurture, nurture from nature when describing the reasons some people develop into elite athletes.”

The study, titled Parental sport achievement and the development of athlete expertise, co-authored by Dr. Joe Baker, sport scientist at Toronto’s York University and Australian Melissa Wilson, sought to determine how the sport involvement of parents related to the eventual level of competitive sport attained by their children.

The study reviewed data compiled previously by Wilson that included 229 athletes from Australia and Canada. The athletes were divided into elite (competed internationally), pre-elite (junior international or senior national competition) and non-elite (lower competitive levels) groups and then compared to their parents’ sports activities and achievement (recreational or competitive). Highlights, first reported in the Montreal Gazette, include:

- Elite athletes were three times more likely than pre-elite athletes to have parents who participated in competitive sport and twice as likely as non-elite athletes to have parents with a history of recreational sport participation.

- Elite athletes were more likely to have parents who, themselves, were elite athletes and who shared the same sport.

- The proportion of parents who participated in sports increased for elite athletes compared to non-elite athletes.

- Parents who competed at an elite level were over-represented among elite offspring and under-represented among non-elite athletes.

- Non-elite level parents were over-represented among non-elite athletes and under-represented among elite children.

- Pre-elite level parents were under-represented among non-elite children.

“The data showed a stronger relationship between the athletic abilities of fathers and children as opposed to mothers and children,” Wilson told Ontennis Magazine in a recent telephone interview. “But I suspect this is because of different levels of sport opportunities for men and women historically and that this is changing over time. It is possible a more recent study would demonstrate a more balanced influence by mothers.”

Wilson added that while the data from the study was clear, it is not a certainty that parental sport participation leads to the same among offspring. “The balance of probability simply suggests that elite athletes, for example, are more likely to have a parent or parents who were really good in their sport. But burn out among young athletes can often be associated with parental pressure. It can work both ways.”

Baker agrees and adds: “Too much pressure and unrealistic expectations from parents and other adults is a good route to failure. This whole process of athletic development is complex. It is important not to put the cart before the horse and to be careful about pressure and expectations.”

The Ingredients

Wilson was asked the ingredients he would use if it were possible to bake an elite athlete in the oven.

“That’s a good question, but a tough one to answer succinctly. I usually think about it as needing the right person, in the right place, doing the right things. An athlete needs genetic gifts physically such as body size, strength and durability. But also mental gifts such as personality. An example of this would be what we often call grit or the ability to stick with something even when it is difficult. This is partially genetic and partially a family value.

“The athlete also needs to be in a place that supports their sport, meaning a country that values it, a city or region with the right resources and opportunities to play the sport and the family that values, supports and provides the opportunities to engage in the sport.

“Finally, even with the right genetics and all the environmental support, the athlete needs a ton of really effective training which, of course, involves more support from family and coaches,” he said.

Birth Age & Relative Age

The birth date of an athlete “absolutely matters,” Wilson said.

“A child born later in the year is likely to be playing sports against children who were born early in the year. This can be a significant disadvantage to the younger athlete, especially in the younger ages. A child born in December, for example, can be competing against others who are almost one year older by virtue of being born in January. There can be significant differences in size, strength and other factors.

"A child born in December, for example, can be competing against others who are almost one year older by virtue of being born in January. There can be significant differences in size, strength and other factors..."

- Melissa Wilson

“As a result, an older child is likely to be better at, say, the age of seven or eight. This might mean they receive better coaching and more opportunities to compete at a higher level. Some younger athletes in this scenario could become discouraged and even quit playing the sport.”

But, he adds, evidence shows this relative age advantage can reverse in the teenage years or by the age of 20.

“If you isolate the best athletes in the world, younger athletes will do better eventually. Halls of Fame in various sports have a significant number of members who are relatively younger athletes. The thought is that they were disadvantaged at younger ages, but they worked harder and pushed more to compete and eventually excelled. That one kid who perseveres through the disadvantages of relative age could end up being excellent at their sport.”

Siblings

Baker is co-author of another study that looked at the family dynamics of athletes. Titled, Sibling dynamics and sport expertise, the study concluded “elite athletes were more likely to be later-born children and that siblings of elite athletes were more likely to have participated in regular physical activity and more likely to have participated in sport at the pre-elite and elite levels.” In other words, siblings can play a key role in athletic development.

“Siblings can be partners for unstructured play and practice in informal environments providing additional opportunities for the development of technical and psychological skills,” the study says. Other highlights include:

- Siblings can not only be training partners, but also competitors.

- Athletes reported siblings were great sources of emotional and instructional support throughout their involvement in sport.

- Some athletes, however, reported anger, disappointment, frustration, anxiety and a sense of pressure to perform better than their sibling.

- Siblings of elite athletes were over-represented at the elite and pre-elite levels of competition while siblings of non-elite athletes were over-represented at the non-elite level.

Other Key Factors

Baker also points out there is a group of people other than parents, siblings and coaches that play a significant role in the development of elite athletes.

“Elite athlete development is a complex web of interactions. All the people in the entire tennis system are involved in some way, form or other. For example, for every elite athlete there are other near-elite athletes they compete against. We don’t always recognize them, but elite athletes would not develop without them,” he said.

Independence is another factor often over-looked, Baker says.

“Children and teenagers are still developing human beings, despite the advanced maturity some might have. At some point, the elite child or teenage athlete needs to develop independently, but know that his or her family is still there for support. They need to be their own functioning human being, making their own decisions. For some elite-level athletes this is not the situation, but the need for independence is true for athletes just like for developing non-athletes,” he said.

Balloon Tennis

Two-year-old Liam Draxl and father, Brian, would bat around an inflated balloon, trying to keep it from floating to the floor. It affectionately became known between the two as “balloon tennis”.

The Draxl / Fortier family

Today, Liam is 19 years old and entering his junior year on tennis scholarship at the University of Kentucky. He finished his sophomore season as the number one ranked men’s singles player in U.S. college tennis and the first ITA National Player of the Year in the school’s history. Not too bad for a balloon tennis player from Newmarket, Ont.

The younger Draxl is not only following in the footsteps of his tennis playing parents, Brian and Alison Fortier, but also laying down an independent path all his own. Currently training in Florida, he is playing small-purse, local pro tournaments to gauge his progress and ranking. He will then decide whether to turn professional or return to school for the spring tennis season.

“We have always talked to Liam about taking small steps and making steady, incremental improvements. Going to college rather than turning pro as a top ten U18 player seemed the next sensible step,” Brian explained.

Brian, born in December like Liam, attended a U.S. university on a tennis scholarship, playing four years at the University of Toledo. He is the long-time head tennis professional at the Newmarket Tennis Club, north of Toronto and was over-45 national singles champion among other accomplishments. Fortier played competitive tennis in the InterCounty Tennis Association.

Liam started spending time at the Newmarket club when his older sister, Stephanie, began taking tennis lessons.

“Liam and his sister have a great relationship that is not really grounded in tennis. While his sister did play college tennis, she does not have the same passion for the game, nor did she ever have the same tennis goals as Liam. For her, it was about getting an education. I think Liam enjoys being able to talk to his sister about many things, not just tennis. She is part of his support system,” Fortier said. “Liam also benefitted greatly from having Brian as his father and coach because being together twenty-four seven just allows for so much more learning opportunity. There were always opportunities to learn even when Liam may not have realized he was.”

Brian Draxl supports the view children should play multiple sports and that their on-court hours should be managed, gradually increasing as they grow older.

“We registered Liam for baseball, soccer and basketball when he was a child, but he kept wanting to go back to tennis. He never asked to play hockey. He had a passion for tennis. I would say he probably played eight to ten hours a day in the summer when he was young, which is too much normally, but it was unstructured play. He would hang around the club most days and make up crazy tennis games to play with his friends,” he said. “They were just having fun. When he was ready to go home his Mom would come and pick him up.”

Researcher Wilson says, “The evidence indicates it is best for children to play different sports and not to specialize if the necessary parental resources exist”, adding that “the best athletes do not specialize in one sport very early.” But, he said, exceptions do exist where the passion for a particular sport is high. “Liam grew up in a great environment with knowledgeable and supportive parents and lots of opportunities to engage in tennis through toys and locations, but he seems to have been given the opportunity to be in charge of how he engaged with it.”

York University’s Baker concluded: “This is an interesting developmental history. It ticks a lot of the current research boxes of things that seem important such as being relatively younger, exposure to lots of sports, but autonomy to choose and lots of support and resources.”

When 11-year-old Brian Draxl began hitting tennis balls for the first time while his parents played recreational doubles on community courts, he would have no idea that the sport would become a major part of his own family’s life and that a tennis prodigy would result from innocent balloon tennis between a father and a toddler.

It's your passion, not our passion

When 13-year-old Simon Bartram moved with his family to Burlington, Ont. in the 1970s it set him, his best friend and eventually his wife and children on a tennis journey he could not have imagined at the time.

Bartram, Tennis Director at The Toronto Lawn Tennis Club today, moved across the street from Tyandaga Tennis Club when he was a youngster. His family became members. Eventually he and best friend, Ari Novick, would “luckily fall in” as the first two participants at the All-Canadian Tennis Academy (now Ace Tennis Academy) in Burlington. Lessons learned at the Academy, owned and operated by Pierre Lamarche, a member of Canada’s Tennis Hall of Fame and former Davis Cup and Fed Cup captain among other notable tennis accomplishments, propelled Bartram to the University of Mississippi (Ole Miss) and Novick to Marquette University on tennis scholarships. Novick continues to serve Tennis Canada as a consultant after announcing his retirement as Senior Director of Tennis Development following a 30-year career.

“My parents played recreational tennis and my Mom played in a league. I would tag along and then get to hit with her when the matches ended. I wasn’t taking lessons at that point, but I was hitting tennis balls off a wall every chance I had,” Bartram recalled during a recent telephone interview.

Today, Bartram’s eldest son, William, 17, has progressed far beyond hitting balls off a wall. He is travelling through Europe with his mother, Maya Bartram, herself an accomplished junior tennis player and graduate of the College of William and Mary where she attended on a tennis scholarship. He is competing on the International Tennis Federation junior circuit, but tennis wasn’t always William’s only sport.

“Both William and his younger brother, Sebastian, are athletic kids. William, like Sebastian now, really enjoyed hockey, but we tried to expose them to a variety of sports. Eventually William came to us saying that hockey was getting in the way of his tennis,” Bartram recalled.

“The parent-child relationship overrides the player-coach relationship. I am aware that ultimately my role is to support and facilitate my son’s journey, which is uniquely his own.”

- Maya Bartram

“But a commitment to tennis is probably 15 hours every week compared to the time involved with a couple of games and a practice in hockey. It’s a heavy workload so we just took it slowly, actually allowing less tennis than he probably wanted just to see if he really wanted badly to do it. He showed us he did. All he wants to do these days is practice and improve,” he said.

Mother, Maya, travelling with William in Europe as both Mom and coach, added: “The parent-child relationship overrides the player-coach relationship. I am aware that ultimately my role is to support and facilitate my son’s journey, which is uniquely his own.

‘When I find myself getting too emotionally involved I use the same techniques I teach him. I come back to my breath and remind myself that I am witnessing his experience, that it is not my own. The more I am able to find an emotionally neutral place from which to witness his matches, the better I am able to help him find his own answers to the challenges that arise.”

William, in a separate email from Europe, explained the tennis backgrounds of his parents gave him great access to the sport. “But I never was under any pressure from them to pursue it. I put a lot of pressure on myself when I was younger, as I still do, to not let my parents down. I’m realizing now that they’re proud of me no matter what I do,”

William is building his ITF junior ranking and with a 69 per cent win rate, according to itftennis.com, is likely to continue climbing the rankings.

Bartram was asked what he hopes for his son.

“As a parent, like most parents, I just hope both boys find their passion in life and take advantage of the opportunities to maximize it, whatever it is. His Mom and I both told William that tennis has to be his passion, not ours. It might be that he has already found his. He has work to do for sure and nobody knows where it will all lead. These are interesting times with lots of uncertainty, but is fun for all of us navigating through it.”

Started on a tennis court, but not playing tennis

Patricia Hy-Boulais could sense when her father, a former Davis Cup player for Cambodia and a teaching pro, or her husband, Yves Boulais, one of Canada’s most accomplished tennis coaches, were sitting courtside during one of her matches. But she learned something from an unexpected source that she would later apply as a Mom to help her own children cope with anxiety, pressure and perceived expectations.

“I was playing Monica Seles, at the DuMaurier Open I think, when I noticed her father sitting courtside. It was like he was watching a movie, not a tennis match with his daughter playing. He clapped for well-played points, not his daughter,” said the former WTA world number 28 and Canadian Olympian.

Patricia Hy Boulais at the DuMaurier Open (now National Bank Open)

“I learned from that and that’s what I try to do when my own kids are playing. I don’t do a lot of celebrating when they play well. One good match isn’t everything,” she said.

Both Boulais children are on their own tennis journey. Isabelle, 21, and Justin, 19, are on tennis scholarships at Ohio State University.

“When I was six years old our family moved from Cambodia to Hong Kong ahead of the Khmer Rouge. My Dad was teaching tennis and my Mom and I would go there after school every day. One day out of the blue I picked up a racquet and started hitting tennis balls. Tennis wasn’t forced on me. It was just the regular exposure to it. It becomes a natural transition,” she explained.

Her own children started their athletic pursuit on a tennis court, too, but it wasn’t playing tennis.

“When we lived in South Carolina I started a program for four- and five-year-old children to teach hand-eye coordination, balance, footwork and similar things in a fun environment. The exercises were done on a tennis court with the thought that it might lead the children through a natural progression into tennis. Both Isabelle and Justin participated. They loved it. They used to cry when they missed it,” she recalled.

Both Boulais children express an interest in professional tennis when their college days are over. Hy-Boulais says the decision is theirs, but she cautions them.

“I say don’t go. It might all seem exciting and glamorous when you’re young, but it is about making a living. That’s hard. You have to be among the top 50 players,” she said.

Hy-Boulais is today a mental coach, helping tennis players to develop personalized mental strengths. On her web site – patriciahy.com – she explains that “the biggest game spoiler that causes players to under-perform repeatedly is pressure.”

It is no doubt an insight she has passed along to Isabelle and Justin. “I am excited when I see them turn agitation over a poor shot or a disputed call into a calm focus. It tells me they can perform.”

Self-imposed pressure, but a life-long love of tennis

Peter Bedard started playing sports other than tennis and was enjoying new activities and friends beginning in grade seven at St. Andrew’s College in Aurora, Ont., north of Toronto. It resulted in the end of competitive tennis for the youngest of four athletic brothers in the renowned tennis family of Robert and Ann Bedard.

“I was in a tennis program outside of school and it started feeling like work. I mentioned to my parents that I wasn’t enjoying tennis training and that was that,” Bedard told Ontennis Magazine recently.

“If there was pressure at the time because of the tennis history in our family, it was self-imposed. My parents were always supportive,” he added.

But he didn’t stop completely. “I do love to play tennis. It has always been fun to play with my brothers and the whole family used to spend our Sundays on the tennis court together,” he recalled.

He returned to competitive play in his 20s while completing a Master’s degree at Toronto’s York University. He was inducted into the York Sports Hall of Fame in 2017. He helped the team win two OUAA championships and was a three-time conference all-star, the first player in program history to earn the honor three times. He also won four OUAA medals including three golds.

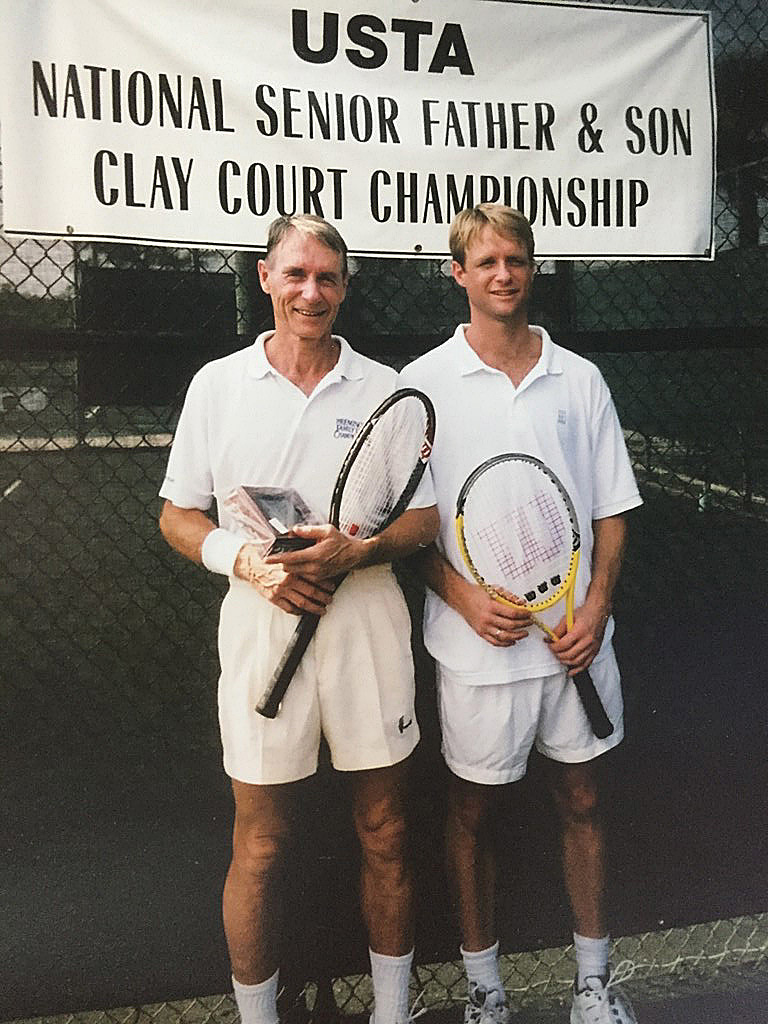

Father Bob and son Peter Bedard

In later years he teamed with his father, Robert, to win four U.S. clay court Senior National Father-Son championships.

“When we were kids, my Dad would not usually comment on technique, but would discuss strategy. Along with my Mom (Robert’s partner in mixed doubles at Wimbledon), my brother Paul provided coaching. Today, he is part of my son Tanner’s inner circle.”

Eighteen-year-old Tanner will be heading off to Niagara University in the fall on a tennis scholarship, following in the tennis footsteps of not just his father, but his mother, too.

Peter’s wife, Jane Bedard, was an accomplished junior player and earned a tennis scholarship to Coastal Carolina University. She has been a teaching pro for more than 30 years.

“We aren’t permitted to say a word to Tanner about tennis,” Bedard chuckled over the telephone. “I would like to have a relationship with tennis like he does. He just takes such a classy approach to the sport.”

Bedard still competes in senior tennis and stays in touch with contemporaries such as Brian Draxl, Simon Bartram and others. “I have so much respect for their attitudes with their kids. They know how and when to hold it back. They’ve lived it.”

With a grandfather who is one of Canada’s most accomplished tennis players and whose multitude of successes resulted in being named an inaugural member of Tennis Canada’s Hall of Fame in 1991, Tanner Bedard has a family history in competitive tennis to build on. And, like his father before him, has knowledgeable and supportive parents to lean on.

He disrupted his older brother’s practices

A young Denis Shapovalov would run on the court and disturb the practices his older brother Evgeniy was having with their mother Tessa, who competed on the Russian national tennis team, played professionally in the 1990s and operates her own tennis school in Richmond Hill, north of Toronto. He disturbed the practices so much that at the age of five his mother told him it was time he started playing if he wanted to.

He did…and then some.

The younger Shapovalov recounted the story to atptour.com a year ago when he was ranked world number 16. Today, he is world number 10 after suffering a close, hard fought, three-set defeat to world number one, Novak Djokovic, in the semi-finals of this year’s Wimbledon championships.

Shapovalov told atptour.com that he wants to “inspire the young generation of Canada to pick up racquets and believe they can become tennis players while living and training in Canada.”

Some Ontario tennis families are listening.

“This is neat stuff,” said the University of Ottawa researcher Stuart Wilson. “You can start to see the same themes coming through (from all of these families). What stands out to me is the role of the passive environment where opportunities such as equipment lying around, tennis clubs across the street, hanging out on the courts are present, but not necessarily forced on the athletes. This lets them choose how and when to engage with those opportunities. Obviously, not every kid is interested in such opportunities and these are kids who decided to engage and to keep it up, which probably says something about their personality, their parents as role models and maybe a little explicit pressure or instruction.”

Wilson’s colleague Dr Baker agrees: “You can start to see some of the general trends here, most of which are supported in the research. Things like the importance of support, access to key developmental resources. But you can also see the athlete-specific nuances which speaks to the ‘no one size fits all’ model of development. Yes, there are key universals such as developing autonomous motivation and providing support, but the pathway is highly individual.