Daniel Nestor’s stunning upset of Sweden’s world number one Stefan Edberg in 1992, Vasek Pospisil’s singlehanded heroics to beat Israel and propel Canada back into the World Group in 2011 and Pospisil and Denis Shapovalov’s run to the final against Spain in 2019 are recent highlights from Canada’s annual hunt for the Davis Cup.

But there were lean years, decades even, from the early 1900s until 1990 when the country made its first World Group appearance following its creation in 1981.

Those lean years were not without their notable rubbers, or matches, and great players, however. One such match in the 1976 Davis Cup was played on Oct. 17, 1975 at the Rockland Centre, Montreal. It was contested into the wee hours of the morning and the second set remains a record for games played in a single set in the 120-year history of the Davis Cup.

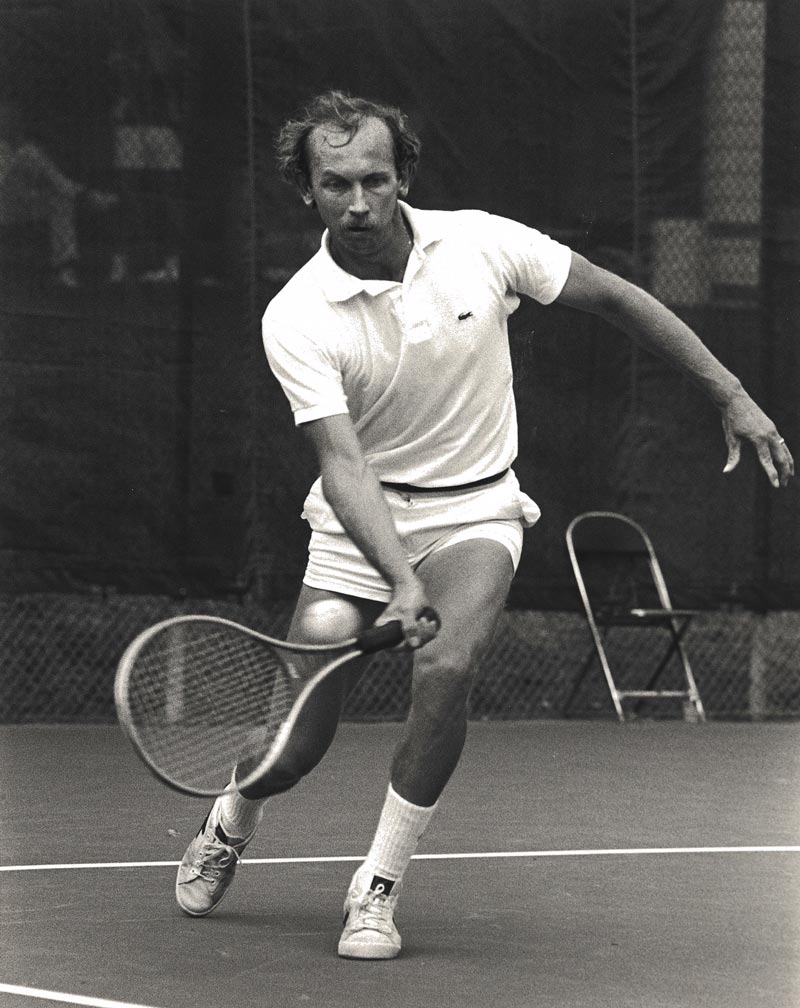

Dale Power, ranked number three in Canada and with no international ranking at the time, faced off against the Colombian team’s top player and third-ranked in that country, Alvaro Betancur, in an Americas Zone North tie. Betancur was ranked 68 in the world, according to www.atptour.com.

Power had just returned to full-time tennis about one year before the Davis Cup tie. He had been on a tennis scholarship at Oklahoma City University from 1970 to 1973 and decided to try professional hockey after he graduated. He attended a walk-on tryout with the Fort Wayne Komets, an affiliate of the NHL’s Pittsburgh Penguins. He not only made the team but was a leading scorer in the 1973-1974 season with 29 goals and 36 assists. A knee injury ended his hockey comeback the following year. He had been drafted by the Montreal Canadiens in the 1969 NHL Entry Draft.

Betancur advanced beyond the first round of the U.S. and French Opens during his career and had wins against notable players such as Nick Saviano and others. His highest ATP ranking was 60 and he represented Colombia seven times in Davis Cup. A recent article on www.daviscup.com refers to him as a candidate for Colombia’s all-time Davis Cup “Dream Team” and describes him as an “excellent player”.

Power won the first set against Betancur 6-4 and dropped the record-setting second set 22-24. The third set went the Colombian’s way 6-2, but Power rallied to win the final two sets 6-3 and 7-5 in five and a half hours. The match ended at 2:30 a.m.

The record-setting second set was equalled during a USSR/Netherlands tie in 1987. Set tie breakers were not introduced to Davis Cup until 2016.

Absorbed Spectator

Power recalls there being “maybe 50 to 100 spectators” when the match finally ended early in the morning of October 18. One of them was Ken Dryden, Montreal Canadiens’ Hockey Hall of Fame netminder. Power recalls Dryden speaking with him after the match, but amid the excitement and exhaustion says he can’t remember the details of the conversation.

Power play a total of 12 Davis Cup matches for Canada between 1972 and 1980

“I asked Dale about his shoulder after the endless serving in that match. I was interested to know what that felt like,” he recalled during a recent telephone interview.

“It was an absorbing match,” Dryden continued. “It was as if the match, itself, didn’t want to end. I kept thinking at some point I have to get home. I’m pretty sure we had a game the next night at the Forum. But it was like a conspiracy. It just wasn’t ready to be over. The two players recognized they had put so much into it that it was unacceptable to lose.”

The Canadiens did play later that night, tying the Philadelphia Flyers 2-2.

Power recalls the Canadian team was confident going into the tie against Colombia, but he added they didn’t know a lot about Betancur other than his ATP ranking. Anecdotal information suggested he was a strong baseline player with consistent, accurate strokes.

“Alvaro, as it turned out, had an all-court game. He had a consistently accurate serve, very solid baseline game and excellent return of serve. He was a superb match player. That match was my first big win. To tell you the truth, I don’t know how I won,” he said.

Managing the mind and emotions

Power and Betancur talked with www.ontennis.ca about that record-setting Davis Cup match and provided insights for recreational and club players about managing the mind and emotions in tennis.

“Those were the days of wooden racquets. I was an all-court player and a good volleyer. I didn’t want to get into long rallies from the back with him because we thought that was his strength. Having a plan is important. Mine was to get to the net as often as possible and make him pass me. And, of course, hold my serve.

“I wanted to play my strength against his and try to make him play my game. That meant get to the net, hit a deep first volley and establish a pattern of play while watching for patterns from him. Understanding your own strengths and weaknesses is key.

“A big part of competitive tennis is mental. Try to make your opponent play your way. Of course, he is trying to accomplish the same thing. That is what makes it challenging.

“Most players have a side they prefer. Find out in the warm-up by hitting to both sides. Look for things such as your opponent’s grip. If it’s a western forehand, for example, you can assume volleying will be difficult. Once you have determined strong side, weak side, play to his strength to open his weakness.”

Handling pressure

Billie Jean King famously wrote: “Pressure is a privilege.”

Betancur says it was experience that helped him manage the pressure that night in Montreal and in other matches. “It was a long match against a great player like Dale Power. The pressure is the same whether you are playing number one or two in Davis Cup. Playing tournaments teaches you how to compete and manage emotions, which gives you a great direction in life,” he said.

Power added: “Pressure is always necessary to enhance one’s performance. I used to handle it by constantly analyzing my opponent’s strengths, weaknesses and strategies and by attempting to be the most consistent player possible. Return any ball that bounces on your side of the net, or that you take in the air, whether it is defensively, aggressively or just getting it back. You can’t be afraid to see a winning shot from your opponent.

“And be as congenial as possible with all officials. They can disrupt your concentration. Try to make sure they like you,” he added with a chuckle.

A big part of competitive tennis is mental. Try to make your opponent play your way.

Nerves and determination

Power had played one Davis Cup tie in doubles in 1972. This match was his first singles encounter. He admits to being nervous.

“Oh ya, I was terribly nervous before the match. I wasn’t expected to win, but I was fired up. It was a big opportunity for me. I was playing for my country. This is it,” he said.

Betancur was nervous as well. “You are always going to be nervous no matter what the competition. It’s good to be nervous because you care. After a little while you get used to the nerves and the competition. The competition takes over from the nerves.”

Power agrees. “Honestly, I never went on court without being nervous. I think nerves can help you play well. You begin to calm down after a few games and start to be more analytical. I think it is difficult to play well without some nerves. The key is to control them and that’s where competitive determination comes into play. It’s about finding a balance between not wanting to lose and not wanting to win too badly. Play point by point,” he said.

Tennis coach David Sammel, author of the book Locker Room Power: Building an Athlete’s Mind, echoes Power’s advice.

“Preparing for a match is so much easier if you know you always compete for small victories and none come smaller than each point. In tennis, if you think you can’t win a match, win a point. Many a match has been won by one point, changing the momentum and a quick return or loss of confidence by one or both players,” he wrote.

“It takes time to learn the mental side of tennis,” Power added. “Play lots of matches. You need competition so find an environment where you can compete.”

Confidence

Confidence is the belief you can reach your objectives in a given situation, according to a blog from the Mouratoglou Academy, a well-known tennis training facility in France.

Lack of confidence, negative thinking, results in a “backward shift of your center of mass (more weight is carried on the rear foot) and a stiffening of the body (which becomes unbalanced and falls backward). When this happens you no longer have enough power to hit the ball and you compensate with the arm. This is when your balls become shorter and your opponent can get the ball earlier.

“When you are confident,” it reads, “it is easier to concentrate, increases your perseverance and effort, influences how you choose your shots and makes a player feel more optimistic and realistic.” It gives a tennis player the feeling “that the ball is bigger than usual and that you are two seconds ahead of your opponent.”

After the first set 6-4 win against Betancur, Power says his confidence soared.

“I am going to win this match” is what he remembers telling people before play started. “After the first set my confidence grew. I thought to myself that I can play with these guys. Winning the first set is so important. It eased the pressure. I worked harder.”

He had to. The second set consisted of 46 games, took more than two hours to play and he lost, 22-24.

“I could have won that set a few times, but I lost my serve. “At that point, I was distraught, exhausted mentally and physically. Then I lost serve at 2-2 in the third set, losing 2-6. I just wanted to get out of there. I was drained. I couldn’t think straight. It was after midnight.”

There was a 30-minute break between the third and fourth sets when Power had a quick shower and tried to re-group. That’s when he received a small piece of advice that made a big difference in the match and stays with him to this day.

Simplify

Mark Cox, a well-known and respected British player who would ascend to 13 in the ATP rankings in 1977, was Canada’s assistant (on court) captain for the tie, responsible for on-court training.

“I was physically and mentally down at that point. Mark said two things. He reminded me I had just beaten my opponent 30 times in the last few hours. And then he told me to focus on holding serve and just see what happens.

“In other words, simplify. Clarify. Good advice, especially when you are physically and mentally tired. I put my nose to the grindstone, my ground strokes improved, I held serve, broke in each set and won the match.

Betancur simplified as well. “I was up two sets to one and lost the fourth set. But the match was not over. So, I fought for every point. You need to focus on every point to make your mind strong and to compete as best you can because you can always take care of business at the end. If you lose, well, you have tried your best.”

Canada eventually won the tie 5-0 and then lost 3-2 to Mexico in the next round. Power’s 6 and 2 singles record in Davis Cup play is still the highest winning percentage among Canadian players. He is 8-4 overall as a seven-time member of Canada’s Davis Cup team.

Improve skills, build confidence

Today, Power, 71, is a tennis professional at the Granite Club in Toronto.

Power has imparted his knowledge and experience to countless young players in his 40 plus years as a tennis coach

“I’ve been teaching tennis for 40 years and it often seems recreational players are happy if they develop a forehand and a bit of a serve. But the better players work on other things including their weaknesses. It still bothers me not to see people developing a full-court game.

“Some of that has to do with equipment. The new racquets and strings have made many recreational players better, but you could argue have made the pro game more boring.

“Learn to work on things you don’t like to work on. Don’t stop working on weaknesses. Repetition. In tennis, consistency is an intangible, an attitude about refusing to lose. You have to learn to play at a certain level and then never go down.”

Betancur is in his 35th year coaching at the prestigious Saddlebrook Preparatory Academy near Tampa, Florida. He is an “incredible teacher”, says Steve Getchell, a tennis pro who worked at the Saddlebrook complex. “He is a workhorse spending many hours on the court. He stays tough on footwork and preparation. He probably played that way, too. There were not a lot of world class Colombian tennis players in his day. I was told he was considered a national hero when he played.”

Power and Betancur agree that being a good tennis player is about more than physical skills.

“There are many great athletes. But being good is not just a physical thing. You have to build the mental side, too. It helps if you are a competitive individual with a real desire to improve your game. Improving your skills helps to build confidence,” Power said.

Betancur added that “You try to motivate and stay positive as best you can. Emotions take time to learn how to manage. Learning discipline and how to manage emotions is a great lesson in life that helps you grow as a person. Tennis is the best university.”

“And, by the way,” Power added, “String your racquet at 42 or 43 pounds, never over 45. You’ll volley better and build an all-court game.”

Dale Power is a former national singles and doubles champion, both indoor and outdoor, at the junior and men’s levels. He is a member of the OCU Sports Hall of Fame and Canada’s Tennis Hall of Fame. Click here to learn more about his accomplishments and career.

Tennis is a global sport, but a small world. Power, Dryden and the writer are all acquainted through sports, but not from playing tennis. They have not had occasion to speak to one another for decades prior to the research for this story. Getchell and the writer are friends, which led to tracking down and connecting with Betancur for an interview. Power and Betancur have not met nor spoken since that memorable match in Montreal 46 years ago. They have each other’s telephone number and plan to get re-acquainted.