Fichman, who childhood friend and training partner Laura Borza calls “something of a prodigy with incredible results” as a junior tennis player, stepped away from professional tennis in 2016. Fichman was dealing with injuries, mental fatigue and a growing interest in activities outside the world of professional tennis. One of those interests was broadcasting and another was coaching.

“I was always motivated by the desire to win as a competitive tennis player,” Fichman said during a recent telephone interview from a temporary residence in St. Petersburg, Fl where she is recovering from a shoulder injury sustained on the Australian leg of the WTA tour. “But coaching provided the opportunity to enjoy tennis in a different way. It gave me a new perspective, helped me see there is more to life than tennis and that there is joy in the process, not just the outcome.”

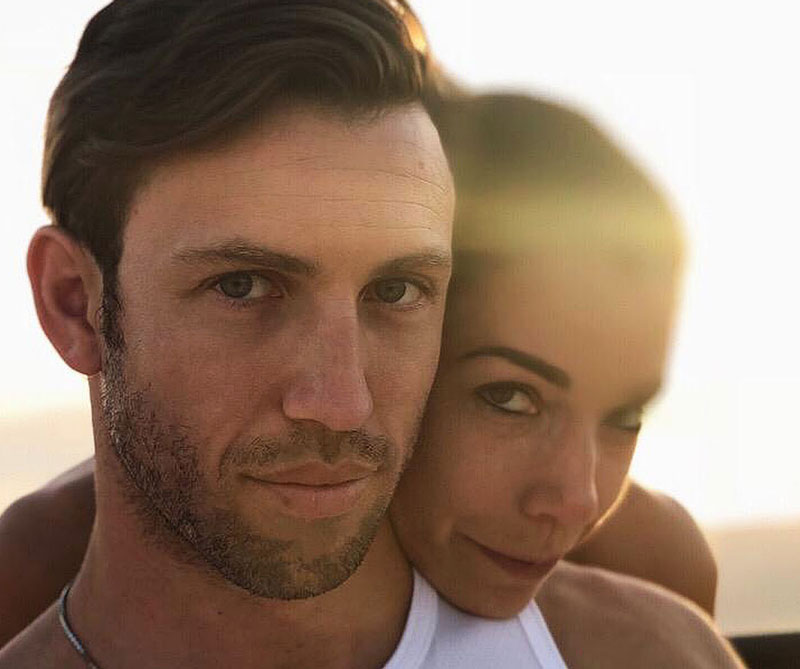

Fichman’s fiancée, Dylan Moscovitch, a decorated pairs figure skater who counts a 2014 Olympic silver medal among his national and international successes, also played a key role in her decision to return to professional tennis.

A sporting couple! Fichman with fiancée Dylan Moscovitch, an Olympic medalist in Pair Skating.

She refers to Moscovitch as a “pathological optimist” and says: “He helped me realize that sport is more than wins and losses. He pointed out there is joy in the process and there are worse things than hitting tennis balls for a living.”

“Dylan encouraged Sharon to finish her career on her own terms with playing in the Olympic Games as a goal. I know she loved coaching, but deep down I think she missed competitive tennis,” said Borza, a tennis professional at the Toronto Cricket Skating and Curling Club. She was also Fichman’s coach earlier this year at the Australian Open and other tournaments.

The Games of the XXXII Olympiad, originally planned for 2020, have been re-scheduled to this summer as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. They are slated to run from July 23 to August 8. The Olympic tennis tournament will be July 24 to August 1 at the Ariake Tennis Park, Tokyo.

The qualification process for the Tokyo Games is based on ATP rankings for men and WTA rankings for women. There will be 56 direct qualifications per gender in singles, 64 in doubles and 32 for mixed doubles. Players can accumulate ATP or WTA points until June 7 this year. The International Tennis Federation will confirm the names of qualified players to national Olympic committees by June 10 and the committees will confirm these choices by June 17, according to www.tokyo2020.org.

Fichman was ranked 54 on the WTA Tour at the time of writing. She and partner Giuliana Olmos of Mexico reached the quarter finals of the Australian Open women’s doubles competition earlier this year.

Fichman and partner Maria Sanchez of the USA hold up the ASB doubles trophy in New Zealand, January 2014.

Simon Bartram, Tennis Director, Toronto Lawn Tennis Club, was involved in helping Fichman attain the necessary coaching credentials that led to a high-performance coaching position at Toronto’s Granite Club. He also played a training role in Fichman’s return to the WTA doubles tour months later.

“I wasn’t surprised when Sharon decided to return to professional tennis. I was happy for her. She was young when she stopped, primarily due to injuries, and I knew she had the ability,” he said. “It was also clear she had the determination when she played ITF tournaments in places such as India to get her ranking back up. That is tough sledding,” he said.

As a young tennis player, Fichman won “pretty much all there is to win.”

As a young tennis player, Fichman won “pretty much all there is to win”, according to Borza. She was national under 18 Champion at the age of 13, played in her first Federation Cup match at 14 and won two Junior Grand Slam doubles titles among other accomplishments. Fichman is still focusing on wins as a professional player, but she says her attitude has changed.

“I’m seeing life these days as infinite opportunities for patience and determination. I have learned to take a deep breath and stick to the process on court. If you build the person, the athlete will follow,” she said.

Fichman in action for Canada in a Fed Cup (now Billie Jean King Cup) tie against Ukraine in 2013.

Support System

Fichman’s return to professional tennis and her steadily improving results are a personal accomplishment. But she is the first person to acknowledge she has not done it by herself. Borza, Moscovitch and Bartram have all played key roles. “I wouldn’t be where I am today without their support. Simon, for example, helped me into coaching and then with training to get back into competitive tennis. I wouldn’t be where I am today without him.”

It is a valuable insight for young tennis players, according to Bartram.

“It is the old expression about it taking a village. Support from parents, a good coach, a fitness trainer, friends, other players is necessary for successful development of a young player. It does require a support system.”

International success! U12 Orange Bowl Champion, 2002.

“Sometimes strong results as a junior player do not translate to professional tennis. You can get wrapped up in success, but if your game doesn’t develop you get stuck on playing the same way and development suffers.”

Borza agrees.

“A young player needs the right people around them to remind of the value in trusting and believing in the process… positive people who will keep a young player from getting down when things don’t go well.”

The Toronto Lawn Tennis Club, where Fichman played from a young age, is an example how clubs can also be an asset in a player’s support system.

“The Club loves the idea of helping its players and is excited to see Sharon doing well. From providing court time and other things it gave Sharon a place to go, to concentrate on tennis and to train,” Bartram explained.

Borza described Fichman as “relentless” as a young player, but as a professional she has learned to be aggressive rather than just “grind out” wins. “It can be tough to understand the need to continue developing your game when you’re winning all the time. But Sharon is pretty intuitive about her career and she has adapted to be successful as a professional player.”

“I needed to lose more as a junior. I didn’t take losing well at all. I didn’t handle it well. I was so focused on results, but there is a lot of value in losing. I eventually realized I had habits that I had to unlearn.”

Fichman sees clearly now what she did not as a successful junior player.

“I needed to lose more as a junior. I didn’t take losing well at all. I didn’t handle it well. I was so focused on results, but there is a lot of value in losing. I eventually realized I had habits that I had to unlearn,” she said.

A Good Coach

Bartram calls Fichman “an extremely good coach” because she has been a dedicated professional player who realizes there are no shortcuts and understands what needs to be done to develop a young player.

The winning started early! Fichman won the 2002 Ontario Junior Outdoor U18 Singles Championship at age 12!

“Sharon was like a pro as a youngster. She had the proper diet, she took fitness seriously and she trained hard. She was more prepared than most anybody to become a good coach.”

During the recent telephone interview, coach Fichman took time to offer insights and advice to young players and their parents.

- A good coach needs to be patient with kids and understand how to make learning and training fun. A good coach can be a positive addition to a child’s life who helps to mould not just the player, but the person as well. She says to ask the question “Do I trust this coach to help make my child better on the court and off?”

- Focus on development more than winning. “Imagine the player you want to be in your teenage years and work toward being that player and person. Sacrifice winning for development if there is a choice to be made.”

- Even a professional player’s confidence wavers and self doubt can occur. “As tennis players, sometimes we can take our feelings too seriously. Self doubt can grow when your pre-conceived feelings about winning and losing are given too much power. Over analyzing can be scary so zoom in and focus on the small steps. Focus on the next shot or point. Do things in pieces, which, actually, is a good way to live life.”

- Take time off and away from tennis. “It is important to be a kid and to do things other than just tennis. Playing other sports is valuable. Soccer offers footwork and teamwork, throwing a baseball and serving a tennis ball are similar, basketball helps with foot and hand co-ordination and so on. I played some soccer and volleyball, swam and did gymnastics and figure skating.”

- Do not pigeonhole yourself, she adds. “In addition to the physical benefits of other sports, working on the mental aspect is helpful, too. Yoga and Pilates are good for mindfulness. Calm your mind and be comfortable with your own thoughts.”

- Remember that competing in tournaments as a child is challenging. “Competing as a kid can be hard. Your ego and self worth can be so wrapped up in your performances because in tennis you are out there alone. You are vulnerable. But tournament play can also develop toughness and perseverance.”

Bartram, winner of Tennis Canada’s Tennis Professional of the Year, Coach of the Year and other awards, endorses Fichman’s advice for young players and appreciates her willingness to share her vulnerabilities.

“Perfection has not been part of Sharon’s journey. I don’t know any tennis player who does everything perfectly. It is helpful for kids to realize they do not have to be perfect at everything. It is a matter of building your own game style based on your strengths, but with a goal of continuing to improve your weaknesses.”

And as a wiser coach, Fichman no doubt quietly passed wisdom along to determined player Fichman: “Embrace adversity. Do everything you need to do to be the player you want to be in the future.”

It is something she is still working on with her sights set on continuing improvement and a well-earned place in this summer’s Olympic Games.